IRR Modeling: Static vs Growth Scenarios

by AMG

Optimism among bankers is slowly increasing, as a steeper yield curve and gradually thawing loan markets give a glimmer of hope for net interest margins. This optimism is being reflected in many interest rate risk models, with projected income finally looking like it will improve in the coming 12 months. However, as is always the case with models, we need to be aware of what is driving those results. For many of the banks we work with, the current environment of excess liquidity is skewing model results and potentially hiding some earnings risk.

The issues lies with the fact that we almost always measure our risk using a static balance sheet. Why do we assume this? I'll defer to the regulators via the 2012 guidance:

8. When no growth scenarios for measuring earnings simulations are mentioned, can you clarify what no growth means?

Answer: "No growth" refers to maintaining a stable balance sheet (both size and mix) throughout the modeling horizon. Financial regulators are concerned that including asset growth in model inputs can reduce the amount of IRR identified in model outputs. For example, if model inputs predict significant loan growth occurring after a rate shock, new loans are often assumed to be made at higher interest rates. This has the effect of reducing the level of IRR identified by the model. If this assumed growth does not occur, the model would underreport actual IRR exposure.

All of that makes sense, and we stick with static balance sheets as our baseline modeling scenario. We will of course test the impact of growth or mix changes, but measuring against policy limits is always done with no growth. For every dollar that matures, we assume it is replaced in the same category at current market rates. And, as in most models, we assume that current market rates in a flat rate scenario is going to be somewhere very close to where we are currently booking instruments of that type. To see the potential issue with this methodology, let's look at an example from a current client.

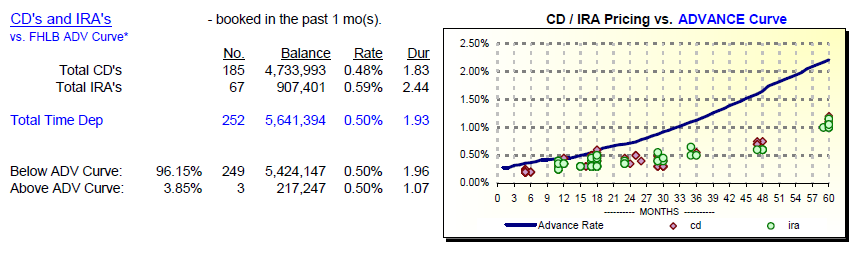

Here is how they priced their time deposits last month:

They did a fantastic job with pricing those time deposits. The dark line on the chart represents the FHLB advance curve, so they were able to generate $5.6 million of deposits at a cost well below the wholesale market rate. This, in a nutshell, is the value of the franchise, as they can use this below market funding to generate positive spreads with little to no interest rate risk.

However, here is the change in the balance sheet over the last quarter:

The bank was able to cut the cost of CDs by 10 basis points and IRAs by 17 basis points, leading to a decline in monthly interest expense (rate driven) of $14,806. Balances, however, dropped by $7.6 million during those same three months.

When assuming a static balance sheet, we forecast that all CD balances will be replaced, and they will be replaced at current market rates (which in most models, is at least very close to the rates at which we are currently booking CDs). Here is what that looks like for this bank:

At these offer rates, CD costs will drop by 28 basis points, IRAs will drop by 26 basis points, and balances will stay the same. The result is that annual interest expense is forecasted to drop by nearly $400k.

However, what rate would we really need to pay to maintain balances instead of shrinking? Can we really expect to cut another quarter point + from time deposits and keep the balances? This anomaly is very likely understating potential interest expense, both in the base case and in rising rate scenarios (since the base rate is used as our starting point in the rate shocks). The same phenomenon is present in many loan portfolios. We are forecasting that our current rates will generate steady balances, when in reality, balances are dropping. What rate would we need to offer to keep those balances steady, and what would that translate to in declining interest income?

This is certainly not a new issue, as we have been facing the same basic circumstances for nearly 6 years now. To this point it has not manifested as bad model results because the balances are not truly leaving the bank, they are simply reallocating to non-maturing deposit accounts that are also at lower rates. However, that will not always be the case, and at that point, we may have a nasty surprise in the form of a much higher interest expense than expected to maintain our balances.

The methodology is not wrong - this is simply one of those issues that we need to be thinking about. The simple solution is to run a quick "what-if" where we up the offer rates (or drop them on loans) to where we think they would need to be to maintain balances. How much does projected income change? As long as we have a handle on that number, we should be able to avoid both the actual surprise and any regulatory criticism of our baseline assumptions.

Let us know if we can help.